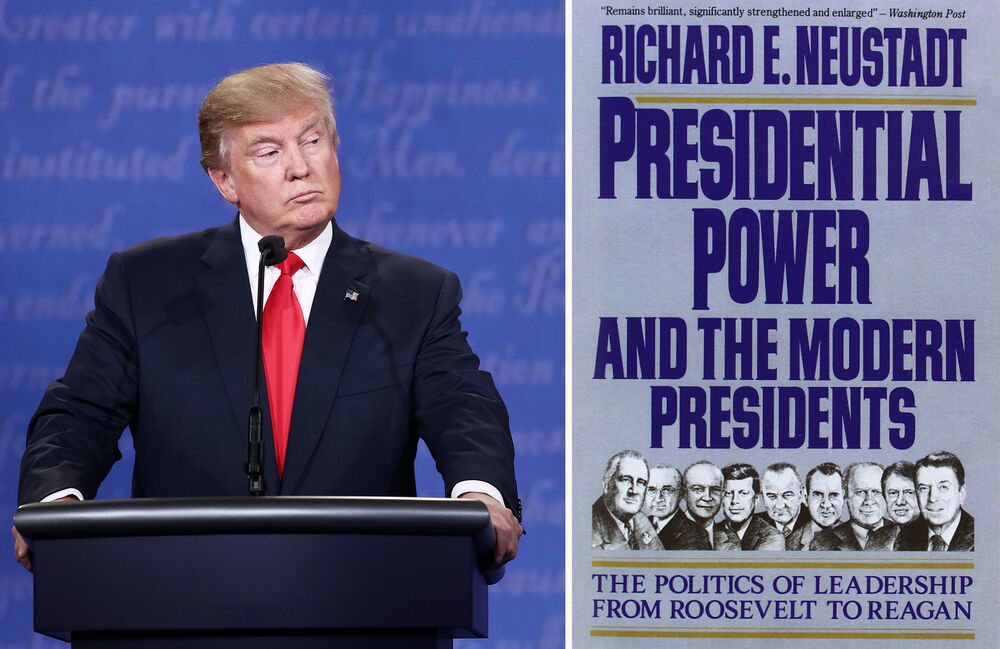

It would have been nice if Republican leaders read this one in 2016. Maybe next time.

by

126

Photographer: Win McNamee/Getty Images

What Neustadt taught was that the constitutional office of President of the United States is an inherently weak one, but that skilled presidents can nevertheless become enormously influential. The flip side of this, however, is that an amateurish president can barely even exercise the constitutional and statutory authority of the office. Neustadt introduces his topic by contrasting the presidency with the way the military appears to operate:

President Truman used to contemplate the problems of the general-become-President should Eisenhower win the forthcoming election. "He'll sit here," Truman would remark (tapping the desk for emphasis), "and he'll say, 'Do this! Do that!' And nothing will happen. Poor Ike -- it won't be a bit like the Army. He'll find it very frustrating."Which, as Neustadt tells it, is exactly what happened:

"The President still feels," and Eisenhower aide remarked to me in 1958, "that when he's decided something, that ought to be the end of it ... and when it bounces back undone or done wrong, he tends to react with shocked surprise." 1It's not hard to imagine Trump there, except instead of shocked surprise the former reality television star apparently prefers temper tantrums and sulking.

Political scientist Dan Drezner argued Tuesday in the Washington Post that Trump is the "weakest commander in chief in modern history" given that he "has no idea how to wield power or issue credible threats." This cluelessness is even more striking given that presidential power over the Pentagon is explicitly spelled out in the Constitution. If Trump has difficulty with getting the military to go along with what he wants -- and he does, as can be seen in their resistance to a transgender troop ban among other things -- then just imagine how little influence he has with every other executive branch agency and department. 2

Without a more direct way to control the government, Neustadt argues that presidents must depend on what he calls "persuasion" -- better referred to as the skilled use of leverage and bargaining power. Not just with Congress, or within the executive branch, but across the board. This "persuasion" doesn't necessarily mean changing anyone's mind. It may just mean convincing someone in a position of power to do nothing rather than something.

Resignations from the president's American Manufacturing Council are a classic case of failed persuasion. The businesspeople who quit -- at least six since the president's poorly reviewed comments on Charlottesville -- were private citizens, not government officials. And all Trump wanted from them, to put it plainly, was for them to do nothing while lending their credibility to his agenda. That's not necessarily a huge ask in the current situation, which didn't directly put the interests of Merck or Under Armour at risk. Yet persuading them to stay put was something apparently beyond the very limited abilities of the president at this point. It didn't help, of course, that Trump reinforced his reputation as a paper tiger by attacking Merck CEO Kenneth Frazier only to have Merck's share prices spike. As my View colleague Joe Nocera pointed out, "there’s nothing to be scared of" from Trump's tweets. Skilled presidents, however, rely on more than just threats. They work hard to build strong relationships, and know when to dangle carrots to loosely affiliated supporters, too.

Or perhaps an even better illustration of how weak Trump has become is that he's even lost, in at least one case, the ability to supply the words coming out of the presidential mouth. Trump resisted the statement originally drafted for him about Charlottesville on Saturday, adding squish words about "many sides" to a statement that would have condemned neo-Nazis. But that didn't stand; by Monday, over his own personal objections, Trump wound up giving the statement he was supposed to have given in the first place. And after kicking up a firestorm in an ugly appearance on Tuesday in which he went back to blaming both sides, it wouldn't be surprising if he winds up backing down again -- or suffering a real price for saying what he wanted to say.

So Trump is, and will remain for the foreseeable future, a historically weak president. His professional reputation is in tatters, he's unusually unpopular, and he doesn't appear to come close to having the skills to do anything about it. Exactly the conditions under which Neustadt predicted presidents would lose influence.

Is that good news for those worried about Trump's preferred policies? In part, sure. But mostly, a very weak president is just a disaster for the nation. As Neustadt argues, presidents are in the best place of anyone within the political system to help produce what he calls "viable public policy" -- basically, government actions that actually work:

If skill in maximizing power for himself served purposes no larger than the man's own pride or pleasure, there would be no reason for the rest of us to care whether he was skillful or not ... But a President's success in that endeavor serves objectives far beyond his own and far beyond his party's.For Neustadt, presidential skill -- and the success presidents have in becoming influential -- are what makes the government work. A "President's constituents, regardless of their party (or their country, for that matter)," he writes, "have a great stake in his search for personal influence."

It turns out, Neustadt contends, that the exact same things which make presidents powerful are also powerful clues to what will make policy successful.

If it is to work, policy needs to be "manageable to [those] who must administer it, acceptable to those who must support it, tolerable to those who must put up with it, in Washington and out." Ignoring those conditions is an invitation to policy disaster; heeding them trims the sails of presidential impulses. This requires a sophisticated view of building consensus on a national level. Presidents must realize:

- Potential allies are equals, not just loyal supporters.

- Opponents are part of the president's constituencies, not just enemies.

- Federal bureaucrats are the ones actually implementing the president's policies, not just obstacles.

- Since Trump evidently is incapable of any of that, he's not likely to improve much in office. Which means we're likely to see presidential weakness as long as he's in office, with high risk of both active and passive policy disaster. It would have been nice if Republican party actors had read their Neustadt before allowing their party to nominate someone this unfit for the office. Maybe next time.

-

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

-

In fact, while Neustadt's theorizing was

excellent, his understanding of both Eisenhower and the army haven't

aged well. Getting things done in the military turns out to be a lot

more complicated and more "political" than Neustadt (and perhaps Truman)

understood it to be, and Eisenhower, whatever frustrations he

expressed, is now thought by historians to have been a very skilled

president indeed. I suspect that Neustadt got Ike wrong because he

expected skilled presidents to act a lot like Franklin Roosevelt, the

(mostly unstated) model Neustadt used for what a good president would be

like. Ike, however, had different assets and different circumstances,

and played the game accordingly.

-

To be sure: Lots of policies are being carried out in

the executive branch that Republicans like and Democrats dislike. Most

of those, however, will turn out to be the agendas of the various people

Trump has nominated, not Trump himself -- and given what we know about

the haphazard way he selected cabinet secretaries and other nominees,

it's unlikely in most cases that Trump intended those particular

policies when he was making the appointments.