Over the last two decades, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) have

become increasingly embedded in militaries around the world. The duties

of these systems range from strikes against insurgents in conflict zones

to surveillance gathering in support of multilateral disaster relief

operations. The commercial sector also relies on unmanned platforms for a

variety of services, including aerial photography, crop monitoring, and

infrastructure inspection. Amid its ongoing economic development and

military modernization, China has emerged as one of a handful of global

leaders in the development of unmanned systems. As China continues to

advance its UAV technology, it is poised to play a dominant role in

shaping industry trends.

The Rise of Drones

While the use of unmanned platforms continues to grow, there is no universal standard for classifying these systems. Defense agencies, civilian organizations, and drone manufacturers often use their own categories, often grouping systems by either their function (e.g. reconnaissance) or key characteristics (e.g. operational altitude). The scheme employed by the US Department of Defense (DoD) favors the latter, and divides drones into five groups detailed below.1| DoD Classification of Unmanned Systems | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Maximum Gross Takeoff Weight (lbs) | Normal Operating Altitude (ft) | Airspeed (knots) |

| Group 1 | 0-20 | <1 agl="" td=""> | <100 td=""> |

| Group 2 | 21-55 | <3 td=""> | <250 td=""> |

| Group 3 | <1320 td=""> | <18 msl="" td=""> | <250 td=""> |

| Group 4 | >1320 | <18 td=""> | Any airspeed |

| Group 5 | >1320 | >18,000 | Any airspeed |

| *AGL = Above Ground Level **MSL = Mean Sea Level | |||

| Source: Department of Defense | |||

As its military modernization has progressed and its position as a

global arms exporter has expanded, China has carefully factored

unmanned systems into its strategic planning. In its 2015 Defense White Paper,

Beijing noted that “military affairs [are] proceeding to a new stage”

and that “[l]ong-range, precise, smart, stealthy and unmanned weapons

and equipment are becoming increasingly sophisticated.” President Xi

further remarked in March 2016 that “UAVs are important operational forces for the modern battlefield.”

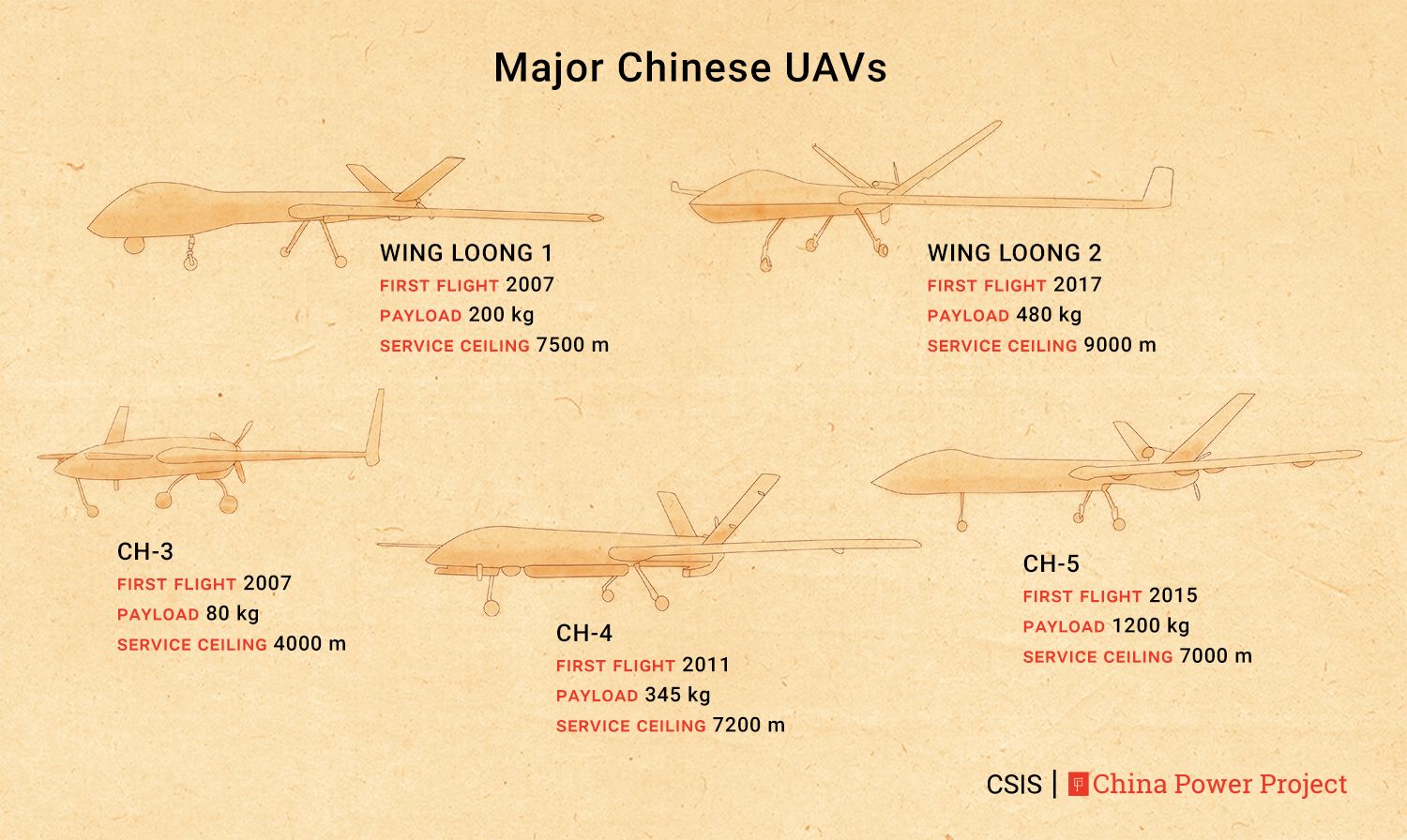

China has found success in producing both strike-capable systems and unweaponized systems for intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) missions. A 2017 DoD report noted that “China’s aviation industry has advanced to produce . . . modern reconnaissance and attack UAVs.” Its Wing Loong and Caihong (CH)2 series have become popular exports to militaries around the globe. Its fleet of reconnaissance drones includes the High Altitude Long Endurance (HALE) Soaring Dragon and Cloud Shadow.

China has found success in producing both strike-capable systems and unweaponized systems for intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) missions. A 2017 DoD report noted that “China’s aviation industry has advanced to produce . . . modern reconnaissance and attack UAVs.” Its Wing Loong and Caihong (CH)2 series have become popular exports to militaries around the globe. Its fleet of reconnaissance drones includes the High Altitude Long Endurance (HALE) Soaring Dragon and Cloud Shadow.

China has made considerable progress in establishing itself as a leader in global arms sales, particularly drones. Learn more about its growing arms exports around the world.

While there are no reports of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) carrying out drone strikes, Beijing has utilized drones in a number of non-combat scenarios.

Following the 2008 Sichuan Earthquake, China used drones to support

various human assistance/disaster relief operations. Chinese law

enforcement has also employed drones to conduct surveillance operations in Xinjiang. In October 2017, China carried out a test flight of an amphibious drone that could potentially ferry supplies to military installations in the South China Sea.

How the CH-5 Drone Stacks Up

While China produces several types of UAVs, its multi-role strike capable drones see the most widespread use overseas. To better serve the growing needs of the international market, China developed the Caihong 5 (CH-5) Rainbow. The new strike-capable UAV is now production ready, and is expected to compete with American Reaper and Israeli Heron TP.

In both size and form, the CH-5 is almost identical to the Reaper.

Both UAVs feature a V-tail and ventral fin. Both measure 11 meters (36

ft) in length and have similar wingspans. Israel’s Heron TP varies considerably

in design. It is configured with a twin-boom tail structure and a pair

of vertical tail fins. It is also larger, with a wingspan of 26 meters

(85 feet), several meters longer than either the Reaper or Heron TP.

The Maximum Takeoff Weight (MTOW) of the CH-5 is approximately 3,300 kg (7,275 lbs), which is about 1,500 kg less than the Reaper and 2,100 kg less than the Heron TP. The lower MTOW of the CH-5 limits the ordinance it can carry when compared to its American and Israeli counterparts. The Reaper can be equipped with a variety of payloads, but it typically carries several hellfire missiles and two 227 kg (500 lbs) bombs.

While it is unclear how the CH-5 will be outfitted, its payload capacity stands at 1,200 kg (2,646 lbs), roughly 500 kg (1,103 lbs) less than that of the Reaper and 1,500 kg (3307 lbs) less than the Heron TP. The newer Avenger UAV, which was designed to succeed the Reaper, has an even more impressive 2,948 kg (6,500 lbs) payload. While operationally ready, the Avenger has yet to gain widespread traction with either the US military or as an export.

The Maximum Takeoff Weight (MTOW) of the CH-5 is approximately 3,300 kg (7,275 lbs), which is about 1,500 kg less than the Reaper and 2,100 kg less than the Heron TP. The lower MTOW of the CH-5 limits the ordinance it can carry when compared to its American and Israeli counterparts. The Reaper can be equipped with a variety of payloads, but it typically carries several hellfire missiles and two 227 kg (500 lbs) bombs.

While it is unclear how the CH-5 will be outfitted, its payload capacity stands at 1,200 kg (2,646 lbs), roughly 500 kg (1,103 lbs) less than that of the Reaper and 1,500 kg (3307 lbs) less than the Heron TP. The newer Avenger UAV, which was designed to succeed the Reaper, has an even more impressive 2,948 kg (6,500 lbs) payload. While operationally ready, the Avenger has yet to gain widespread traction with either the US military or as an export.

Like other Chinese aviation platforms, the CH-5 is limited by its engine. As

a result, the multi-role striker flies at a max speed of 120 knots –

more than 100 knots slower than the Reaper and Heron TP. Compared to the

Avenger, which boasts a max speed of 400 knots, the limitations of the

CH-5 are even more pronounced. The CH-5 also flies at a lower altitude, reaching

just 7,000 meters (22,965 ft), far below the 15,000m (50,000 ft)

ceiling of the Reaper and 13,716m (45,000 ft) ceiling of the Heron TP. The CH-5’s limited ceiling makes it more vulnerable to anti-aircraft weaponry.

To help compensate for these issues, the CH-5 can be outfitted with an optional heavy-fuel engine that extends the craft’s operational endurance to 60 hours – a 20 to 30 percent boost from its standard engine. This is more than double the Reaper’s fly time of 27 hours, and still significantly longer than the Heron TP’s 36 hours.

To help compensate for these issues, the CH-5 can be outfitted with an optional heavy-fuel engine that extends the craft’s operational endurance to 60 hours – a 20 to 30 percent boost from its standard engine. This is more than double the Reaper’s fly time of 27 hours, and still significantly longer than the Heron TP’s 36 hours.

According to state media reports, the CH-5 can be “operated by an undergraduate student with basic knowledge of aviation after only one or two days of training.”

Longer endurance gives the CH-5, in theory at least, an edge in

its operational range. Paired with the heavy-fuel engine, the CH-5 has a

manufacturer reported range of 6,500 to 10,000 km (4038 to 6,214

miles). Nevertheless, China’s limited command and control capabilities

may in practice limit the CH-5’s operational range to under 2,000 kilometers (1,243 miles).

The CH-5 features a range of electronic warfare systems that are comparable to other UAVs, including infrared/electro-optic and thermal imaging capabilities for air-to-ground intelligence gathering. The CH-5 can also identify targets through walls, furthering its capacity to carry out missions in urban settings. One of the CH-5’s most notable features is that it shares a control system with its predecessors, the CH-3 and CH-4, enabling joint strike operations. According to state media reports, the drone’s autonomous flight option drastically reduces the learning curve for operators, allowing the drone to be “operated by an undergraduate student with basic knowledge of aviation after only one or two days of training.”

The CH-5 features a range of electronic warfare systems that are comparable to other UAVs, including infrared/electro-optic and thermal imaging capabilities for air-to-ground intelligence gathering. The CH-5 can also identify targets through walls, furthering its capacity to carry out missions in urban settings. One of the CH-5’s most notable features is that it shares a control system with its predecessors, the CH-3 and CH-4, enabling joint strike operations. According to state media reports, the drone’s autonomous flight option drastically reduces the learning curve for operators, allowing the drone to be “operated by an undergraduate student with basic knowledge of aviation after only one or two days of training.”

Chinese Drones Around the World

China has quickly emerged as a major exporter of multi-role strike capable UAVs. Between 2008 and 2017, China exported a total of 88 drones to 11 different countries. Over three quarters of these sales were of strike capable systems, including those of the popular Caihong (50 percent of sales) and Wing Loong (26 percent) series. The newest Caihong model, the CH-5, is expected to build on this success.In terms of total UAV sales, however, China lags other exporters. Since 2008, the US has sold 351 drones to partners around the world, followed by Israel’s 186 UAV exports. The majority (82 percent) of US sales have been composed of ISR drones, ranging from the mini-surveillance drone Scan Eagle up to larger platforms like the Global Hawk. Roughly 70 percent of Israel’s UAV exports have been ISR platforms, including the Searcher and Aerostar.

No orders have been placed yet for Chinese HALE drones, and

Beijing rarely exports its smaller surveillance systems. Instead, China

has positioned itself to specialize in exporting strike-capable UAVs.

Between 2008 and 2017, China sold 68 Caihong/Wing Loong series drones,

slightly surpassing the 62 Reaper/Predator drones exported by the US and

the 56 Hermes/Heron TP drones sold by Israel. These numbers are

expected to grow considerably in the coming years. In 2017, China

announced an agreement with Saudi Arabia to build a manufacturing and servicing facility in-country to produce up to CH-4s.

To date, the main purchaser of Chinese drones has been Pakistan (25 percent of sales), followed by Egypt (23 percent) and Myanmar (13 percent). While the United States sells surveillance drones to countries around the world, exports of strike capable drones have been limited to its European and East Asian allies. Israel is less restrictive with its exports, selling strike capable drones across Latin America, South Asia, and Europe.

To date, the main purchaser of Chinese drones has been Pakistan (25 percent of sales), followed by Egypt (23 percent) and Myanmar (13 percent). While the United States sells surveillance drones to countries around the world, exports of strike capable drones have been limited to its European and East Asian allies. Israel is less restrictive with its exports, selling strike capable drones across Latin America, South Asia, and Europe.

China’s exports have benefited from American export controls. The US has historically restricted

foreign sales of strike-capable drones as part of its participation in

regulations like the Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR). The MTCR

is a voluntary multilateral agreement that was established in 1987 to

limit the proliferation of platforms capable of delivering chemical,

biological, and nuclear weapons. As a result of somewhat dated

regulations like the MTCR, many long-range drones have come to be

characterized as cruise missiles. In a push to facilitate greater drone sales, President Trump relaxed export rules in April 2018, but the effect of these changes is yet unknown.

Israel, on the other hand, experiences political limitations instead of legal restrictions. While it has supplied over 60 percent of the world’s UAVs in the last three decades, numerous political and strategic factors have limited sales to Middle Eastern countries.

Israel, on the other hand, experiences political limitations instead of legal restrictions. While it has supplied over 60 percent of the world’s UAVs in the last three decades, numerous political and strategic factors have limited sales to Middle Eastern countries.

The CH-5 is estimated to cost $8 million, roughly half the cost of the American-made Reaper.

Perhaps the biggest draw to Chinese drones is their price tag. The new CH-5 is estimated to cost half that of the $16 million Reaper. The CH-4 and Wing Loong II are even cheaper, estimated

to cost between $1 to 2 million – far less than the comparable $4

million Predator. Countries looking to shore up their security needs on a

budget have been particularly attracted to these systems. For instance,

the Iraqi Defense Ministry opted in 2014 to purchase four CH-4s instead

of the costlier Predator.

These sales and their subsequent use have helped boost the profile of Chinese unmanned systems. On December 6, 2015, the Iraqi Defense Ministry released a video showing a CH-4 variant carrying out a missile attack on the Islamic State (ISIS). Iraqi authorities have reported that since that strike, CH-4s have conducted over 260 air strikes against ISIS targets, with a success rate of nearly 100 percent. The growing visibility of Chinese unmanned platforms is likely to help grow its export profile in the coming years.

These sales and their subsequent use have helped boost the profile of Chinese unmanned systems. On December 6, 2015, the Iraqi Defense Ministry released a video showing a CH-4 variant carrying out a missile attack on the Islamic State (ISIS). Iraqi authorities have reported that since that strike, CH-4s have conducted over 260 air strikes against ISIS targets, with a success rate of nearly 100 percent. The growing visibility of Chinese unmanned platforms is likely to help grow its export profile in the coming years.

The Commercial Drone Market

While China is well-positioned to compete with other exporters of military UAVs, it has already cornered the commercial drone market. Chinese drone companies are estimated to control nearly 80 percent of the market worldwide.Global commercial drone sales totaled $8.5 billion in 2016 and are expected to surpass $12 billion in 2021. Importantly, business prospects for drones go beyond unit sales. According to a 2016 study by PricewaterhouseCoopers, the total value of the industries that could utilize drone technology totaled some $127 billion in 2015. These industries include infrastructure inspection, agriculture, transportation, media and entertainment, and several other sectors.

| Top 5 Drone Brands by Global Market Share (2017) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Brand | Market Share (%) | Country |

| DJI | 72 | China |

| Yuneec | 5 | China |

| 3D Robotics* | 4 | US |

| Parrot | 2 | France |

| Autel | 2 | China |

| Source: Skylogic Research, 2017 Drone Market Sector Report | ||

| *In August 2017, 3D Robotics announced a partnership with DJI. | ||

China’s dominance in the commercial drone industry can be

attributed primarily to one manufacturer, Dà-Jiāng Innovations (DJI).

Due to its speed in producing cutting-edge technology at a low cost, DJI

controls over 70 percent of the market. Its market penetration is so

significant that DJI became the most widely used commercial drone by the

US Army. Due to rising security concerns, however, the US Army discontinued the use of DJI drones in August 2017.

China’s civilian drones sector is increasingly developing drones with military applications. In large part due to reforms introduced in 2013, private companies are now able to compete against SOEs to produce and sell UAVs to the military. Newcomer drone company Tengoen Tech,

for instance, is designing an eight-engine drone that can be customized

for search and rescue, aerial refueling, and intelligence gathering

missions. The blurring of commercial and military UAV development could

serve both sectors. As noted by Jane’s, this marriage has “created a vibrant, active and fast-moving UAV development and, increasingly, innovation environment[.]”

Photo Credit: Power Sport Images/Getty Images