June 19 marked the 66th anniversary since the execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, a young Jewish-American couple from New York City, whose alleged guilt as Soviet “atomic spies” has never been proved—in spite of the numerous lies, forgeries and other hoaxes of white, gray and black propaganda thrown against them since then. Moral absolutists believe that all killing is immoral—except in cases of justified self-defense or perhaps in cases of mercy killings and medically-assisted suicides (“euthanasia”). It is for this reason that all European nations have abolished the death penalty. Except in the ex-Communist countries of Eastern Europe, Europe’s violent crime rate (including its murder rate) has not increased as a result of such a dramatic legal reform (Rachels & Rachels 149-150).

The death penalty is especially controversial and morally indefensible as punishment when applied to bloodless crimes such as military desertion in time of war or “high treason” (espionage) in peacetime. A particularly outrageous “high treason” case was that of Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, who were falsely accused of being Moscow’s “atomic spies” and electrocuted on June 19, 1953 for what FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover bombastically called “the Crime of the Century.” Many years later, an eminent, Harvard Law School-educated legal expert unequivocally concluded that

“The Rosenberg case, as controversial as it was, was also a major miscarriage of justice. No one can be proud of what American justice did in the Rosenberg case. It deserves a special place in the conscience of our society” (Sharlitt 256).

Yet, the “patriotic” zealots, who once railroaded and murdered the Rosenbergs, now want to prosecute and put to death for “high treason” Edward Snowden, the former National Security Agency (NSA) employee and fugitive whistleblower. Thanks to Mr. Snowden we know now that the NSA has been spying on Americans by secretly recording and storing all their private communications. Another possible future target is Julian Assange, the celebrated yet controversial Wikileaks editor and founder—if the Australian journalist of Russiagate fame is ever extradited from Britain to stand trial in the U.S. This article is about the government’s misuse of the death penalty as quasi-legal punishment and a political weapon, as happened in the unjust trial and execution of the Rosenbergs for peacetime espionage—an event which has historically become known as “the peak of the McCarthy Era” (Wexley xiii).

The McCarthy era

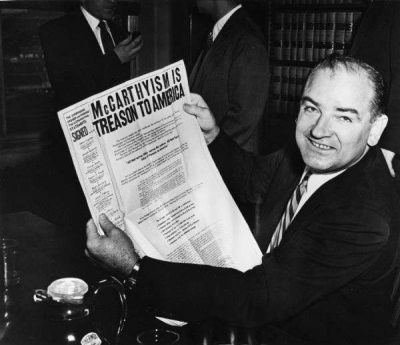

The year 1948 marked the beginning of the era of McCarthyism, the notorious Red-baiting hysteria in postwar America. The term “McCarthyism” was coined from the name of the junior Republican Senator from Wisconsin, Joseph McCarthy. As a member of the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, Senator McCarthy was pursuing Communists allegedly operating from inside President Harry Truman’s Democratic Administration, especially in General George C. Marshall’s Department of State, which was blamed for having “lost China” to Mao Tze-Tung’s Soviet-backed Chinese Communists in 1948-1949. With the help of the U.S. House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), Joe McCarthy wanted to prove that the Truman Administration, which had many “New Dealers” and some left-wing holdovers from the earlier FDR presidency, was riddled with “Communists” secretly spying for Moscow. Even the Truman Administration itself had set up the Federal Employee Loyalty Program and numerous groups like the American Committee for Cultural Freedom to ferret out alleged Communists in government and the mass media (Carmichael 1-5, 41-46).

What made Senator McCarthy especially infamous was his active role in the persecution and imprisonment of thousands of real or suspected American Communists—including nearly 150 leading members of the Communist Party (CPUSA)—for allegedly conspiring to overthrow the U.S. constitutional system in a violent Communist revolution. Under the draconian Smith Act, any American who was a member of the CPUSA could be prosecuted as a traitor and a Soviet spy. Even Hollywood was not spared the nationwide anti-Communist witch-hunts, as hundreds of movie actors and actresses, directors, screenwriters, producers, music composers, publicists and even stage hands were “blacklisted,” fired from their jobs or—like the “unfriendly” Hollywood Ten—imprisoned for their “Communist” sympathies and affiliations (Carmichael 46-47). Some “Dream Factory” celebrities like Charlie Chaplin and Bertolt Brecht chose to flee abroad rather than end up in prison.

Image on the right: Ethel and Julius Rosenberg (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

President Truman had repeatedly assured Americans that the USSR could not acquire a nuclear weapon for the next 10-20 years, so when the Russians tested an atom bomb in August 1949, the hunt was on for domestic traitors and atomic spies working for Moscow. Senator McCarthy and the equally infamous assistant prosecutor Roy Cohn, who served as chief counsel to the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, publicly accused many known and unknown “Communists” of atomic spying for the Soviet Union. One of the accused was the obscure owner of a small machine shop in New York City named David Greenglass. Mr. Greenglass had been a young army sergeant assigned to the Manhattan Project in Los Alamos, New Mexico, where America’s first atom bombs were being developed during World War II. Cohn’s accusations against him were totally unsubstantiated, as there was “not a single witness or a shred of supporting evidence that Greenglass had committed any espionage” (Wexley 113-114). But panicked and fearful for his life, Greenglass falsely implicated his sister Ethel and her husband Julius—as he woefully admitted many years later—at the urging of prosecutors and in order to shield himself and especially his beloved wife Ruth from possible criminal charges of atomic espionage and high treason (Roberts 479-484).

Relying solely on Greenglass’s suspect testimony, government prosecutors had Julius and Ethel Rosenberg arrested, jailed and tried for stealing America’s atom bomb secrets and passing them on to Moscow. In gross violation of the code of judicial conduct, Cohn, trial prosecutor Irving Saypol, and presiding Judge Irving Kaufman illegally consulted each other nearly every day and secretly conspired with other high-ranking officials of the Justice Department, including U.S. Attorney-General Herbert Brownell Jr., to subvert the defendants’ legal defense.

The prosecution fabricated most of the evidence against the Rosenbergs with the cooperation of David Greenglass, who became a government witness in exchange for leniency for his own and his wife’s alleged past activities as Soviet spies (Roberts 476-477). A relatively recent book written by a prominent New York Times editor reveals how Greenglass perjured himself in his damaging court testimony against the Rosenbergs which ultimately led to the conviction and execution of his sister and brother-in-law (Roberts 482-483). Worse still, “no documentary evidence supporting the government claims regarding Julius and Ethel was available to the Rosenbergs or to their defense counsel during the trial” (Carmichael 109). This deliberate omission was a travesty of justice which ”was also an abuse of the Rosenbergs’ fundamental right to know the evidence against them, under the Fourteenth Amendment” (Carmichael 109).

Due to heavy political pressure, especially from Chief Justice Fred Vinson, the U.S. Supreme Court refused to review the Rosenbergs’ convictions for espionage and denied the stay of their executions ordered by Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas for the purpose of reopening their controversial case (Sharlitt: 46-49, 80-81). Though obviously innocent of the charge of being atomic spies, the Rosenbergs were electrocuted at New York’s dreaded Sing Sing Prison on June 19, 1953 despite national and world-wide protests and appeals for clemency on their behalf. Just two months later, a Soviet heavy bomber plane dropped the world’s first operational hydrogen (thermonuclear) bomb in an above ground test, which demonstrated the absurdity of the idea that Moscow needed to steal America’s atomic secrets in order to produce its own nuclear weapons. A revelatory new book summarizes the rather sordid legal details of the Rosenbergs case:

“…a young American Jewish couple declined to make counterfeit confessions to having committed treason against the United States. The husband, out of misplaced idealism, had committed a crime for which his indictment made no claim that he had harmed the United States. That crime was inflated to “treason” by reckless and opportunistic officials, prosecutors and the judge to satisfy a political agenda. To have confessed to the uncommitted crime, for which Justice officials cynically demanded the names of accomplices who would likewise face the threat of execution for an uncommitted crime, was beyond the Rosenbergs’ capacity to satisfy. They would be sending family members and friends to their deaths, making orphans of their children and burdening their futures with an unearned shame.” (David & Emily Alman 377)

Since then, much new evidence has come to light (some of which was previously suppressed by the government or withheld by the prosecution) that confirms the innocence of the Rosenbergs. It is by now widely accepted that Ethel Rosenberg was never a Soviet spy and that the prosecutors knew very well of this exculpating fact. The mother of two young children, she was arrested, jailed and held as hostage by J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI and later sentenced to death in order to blackmail her husband into confessing his alleged guilt and naming other Soviet espionage agents. Apart from a lot of courtroom “hearsay evidence,” never did the prosecution and the trial judge produce in court any hard facts that “proved the existence of a spy ring headed by Julius Rosenberg,” claiming conveniently that all such documentary evidence “had to remain secret for national security reasons” (Carmichael 109).

Julius tried unsuccessfully to defend himself by insisting that his alleged spying during World War II—even if the espionage charges against him were indeed true—was on behalf of America’s wartime Soviet ally and had absolutely nothing to do with stealing any atom bomb information. But the sentencing judge’s legally and factually ridiculous argument that the Rosenbergs had put the atom bomb in Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin’s “bloody hands” which later led to the death of 54,000 U.S. servicemen in the Korean War (1950-1953), carried the day at least in the eyes of the enraged American public and sealed the accused couple’s fate.

But the most tragic thing in the entire trumped-up affair was that the British had already arrested and imprisoned the German-born nuclear scientist Klaus Fuchs, who had admitted to them sending secret information about the American atom bomb to Moscow, while working for the top-secret Manhattan Project in Los Alamos during World War II. The witch-hunting McCarthyites obviously needed a few domestic scapegoats to blame for the development of Stalin’s nuclear arsenal.

If the death penalty for a “bloodless crime” like high treason in peacetime (which President Dwight Eisenhower refused to commute to life imprisonment in their case) had not been on the books at that time, the Rosenbergs would have been later exonerated and freed from prison given the gradual waning of the anti-Communist hysteria. This is exactly what happened to the convicted and incarcerated leaders of the Communist Party, all of whom were—one by one—released from prison by the courts: “By the beginning of 1958, the former Communist Party leaders convicted in 1948 under the Smith Act had been freed; the Supreme Court had overturned their convictions” (Roberts 453).

Conclusion

The case of Ethel and Julius Rosenberg is a glaring example of the corruption and politicization of America’s court system and judicial process in the highly charged Cold War atmosphere of the Fifties. Despite their courage and indomitable will to live as well as strong public support for them at home and abroad, the Rosenbergs did not survive the unconstitutional injustices visited upon them by the politically prejudiced and morally dishonest judicial authorities. The latter were determined to achieve their anti-Communist goals by all possible means, both legal and illegal. The Justice Department had forged much of the damning evidence against the Rosenbergs, while key witnesses in the trial had repeatedly changed their stories after coaching from the prosecutors. As a seasoned trial analyst later wrote about the “unwarranted” conviction and execution of the Rosenbergs: “Given the fear of communism that overtook the United States in the 1950s, it is questionable whether there could have been another outcome…. [T]heir deaths remain a blemish on American society…. [W]hen a nation is swept by paranoia, the innocent suffer along with the guilty” (Moss 97).

Notorious court cases like the Rosenbergs continue to remind the informed public that the death penalty cannot and should never be considered legally justified or morally defensible, especially in non-violent cases like peacetime espionage. Because capital punishment makes it practically impossible to reverse past miscarriages of justice by presenting new or previously suppressed evidence that exonerates the executed defendants. In the case of the Rosenbergs, the prosecution and the courts have stubbornly refused to this day to acknowledge the proven innocence of the defendants and to overturn their wrongful convictions and death sentences.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Rossen Vassilev Jr. is a journalism senior at the Ohio University in Athens, Ohio.

Sources

Alman, David, and Emily Alman. Exoneration: The Trial of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg and Morton Sobell. Seattle, WA: Green Elms Press, 2010. Print.

Carmichael, Virginia. Framing History: The Rosenberg Story and the Cold War. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 1993. Print.

Moss, Francis. The Rosenberg Espionage Case. (Famous Trials series). San Diego, CA: Lucent Books, 2000. Print.

Rachels, James, and Stuart Rachels. The Elements of Moral Philosophy (8th edition). McGraw-Hill Education, 2015. Print.

Roberts, Sam. The Brother: The Untold Story of Atomic Spy David Greenglass and How He Sent His Sister, Ethel Rosenberg, to the Electric Chair. New York: Random House, 2001. Print.

Sharlitt, Joseph H. Fatal Error: The Miscarriage of Justice that Sealed the Rosenbergs’ Fate. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1989. Print.

Wexley, John. The Judgment of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. New York: Ballantine Books, 1977. Print.

The original source of this article is Global Research

Copyright © Rossen Vassilev Jr., Global Research, 2019