by

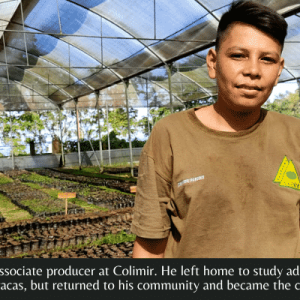

Johandri Paredes is an associate producer at Colomir. He left home to study administration at a military university near Caracas, but returned to his community and became a comptroller at the Che Guevara Commune. Source: Cira Pascual Marquina and Chris Gilbert, "Highland Resistance: How the Che Guevara Commune Confronts the Crisis (Part I)," December 10, 2021.

A big fluffy dog. That is all Simón Bolívar got out of the Andean people when he went there looking for recruits and supplies at the time of the independence wars. The dog, named Nevado, entered the history books, but the coolness of Andean Venezuelans to Bolívar’s project did not. A population of small farmers who owned their land, the region’s campesinos were not willing to sign up for just any abstract proposal that involved much risk and unclear objectives. Moreover, these highland communities were not so leader oriented: in one of the stories told about Bolívar’s visit, the hero of Venezuelan independence got the dog because he asked to be shown their leader!

Just as the independence struggle had different resonances in the Andes, so too does Venezuela’s project of communal socialism. The region is home to one of the most successful communes in the country today, and, like other working communes, this one has a solid productive basis (a chocolate factory and coffee cooperative) and is run by seasoned cadres. However, the Che Guevara Commune is markedly different from others that sprung up in response to Hugo Chávez’s call to build communes as “the basic cells of socialism.” More methodical, cautious, and pragmatic, the communards in these hillsides have built their project little by little, organizing their communities around the production and processing of two labor-intensive cash crops and the know-how they have acquired from cross-border migration.