How China’s Zero-License Policy Created the Most Sophisticated Mineral Warfare Operation in History

By Shanaka Anslem Perera

December 27, 2025

I. THE FORM THAT NEVER COMES BACK

The weapon is not a ban. The weapon is a form.

Somewhere in the bowels of China’s Ministry of Commerce, in the grey bureaucratic machinery of MOFCOM’s export licensing apparatus, there exists a filing system that has received every tungsten export license application submitted by American importers throughout the calendar year 2025. Every single application. Dozens of them. Hundreds, perhaps. From defense contractors scrambling to meet Pentagon specifications. From semiconductor equipment manufacturers racing to maintain wafer production. From industrial toolmakers watching their inventory clocks tick toward zero.

Not one has come back approved.

This is not speculation. This is not inference from supply chain tightness or price movements or anecdotal reports from frustrated procurement officers. This is the documented operational reality of what industry sources confirm as a zero-license policy that has functioned, for all practical purposes, as a complete embargo on American access to Chinese tungsten. No announcement. No formal declaration. No diplomatic incident that would trigger retaliation or international arbitration. Just forms that enter a bureaucratic process and never emerge on the other side.

The genius of this approach is its deniability. When Congressional staffers or trade officials or investigative journalists inquire about the status of tungsten exports to the United States, MOFCOM can truthfully state that no export ban exists. Licenses are available. Applications are welcome. The process continues. It simply happens that every American application remains perpetually under administrative review, caught in a procedural limbo that provides neither approval nor denial, only endless uncertainty that makes procurement planning impossible and inventory management a nightmare.

This is sanctions by paperwork. Low visibility. High plausible deniability. Completely reversible at Beijing’s discretion. And devastatingly effective.

Understanding why this matters requires understanding what tungsten actually is and does in the modern industrial economy. It is not merely another commodity in the critical minerals taxonomy. It is not simply one more Chinese-dominated supply chain among dozens. Tungsten occupies a unique position in the periodic table and an equally unique position in the architecture of contemporary manufacturing. With the highest melting point of any element at 3,422 degrees Celsius and a density of 19.35 grams per cubic centimeter that exceeds lead by seventy percent, tungsten enables applications where no substitute exists and where failure is not an option.

The armor-piercing penetrator that defeats a main battle tank’s composite armor requires tungsten’s density to achieve the kinetic energy necessary for penetration at combat velocities. The chemical vapor deposition process that creates the vertical interconnects in a three-nanometer semiconductor requires tungsten hexafluoride at six-nines purity because no other material can fill the microscopic trenches and vias without forming voids that destroy chip yields. The cemented carbide cutting tool that machines the engine block in every automobile and the turbine blade in every jet engine requires tungsten carbide’s hardness because softer materials simply cannot survive the forces involved.

Sixty percent of all tungsten consumed globally goes into cemented carbides. Every machining operation in modern manufacturing depends on them. No tooling, no machining. No machining, no production. The arithmetic really is that simple.

China produces eighty-two point seven percent of the world’s tungsten. The United States produces zero. Net import reliance stands at one hundred percent. There is no strategic stockpile adequate to bridge more than a few months of disruption. There is no domestic production capacity to restart. There are promising development projects in Canada and Nevada and South Korea, but the nearest of these will not reach meaningful commercial production until 2026 at the earliest, and most face timelines extending to 2028 or 2030.

For the next twenty-four to thirty-six months, the West exists in what can only be described as a gap of vulnerability. Demand exceeds secure supply by a margin that no policy response, no emergency funding authorization, no accelerated permitting process can close before the gap becomes a crisis. The question is not whether tungsten’s strategic importance will be recognized. The question is whether that recognition comes in time to matter.

The price trajectory already tells the story. Chinese tungsten concentrate has rocketed from 143,000 renminbi per ton in January 2025 to 460,000 renminbi by late December. That is a two hundred percent increase in a single year. European ammonium paratungstate, the primary intermediate product that feeds downstream manufacturing, has risen from 340 dollars per metric ton unit to between 880 and 920 dollars. Some traders report transactions above one thousand dollars. The spot market, such as it exists in tungsten’s opaque bilateral trading structure, is in full panic mode.

Yet this price signal, dramatic as it appears, understates the severity of the underlying supply shock. Tungsten has no futures market. There is no LME contract providing transparent price discovery or hedging mechanisms. Trading occurs through private bilateral negotiations between producers and consumers, with pricing information disseminated through industry associations and specialized publications that lag real-time market conditions by days or weeks. The opacity that characterizes tungsten’s market structure amplifies volatility rather than dampening it. Participants cannot hedge. Speculators cannot arbitrage away mispricings. Inventory positions remain invisible until shortages manifest in production stoppages.

The China Tungsten Industry Association itself has acknowledged that current prices have far exceeded the support of real consumption, being largely driven by speculative demand. When the industry’s own trade body warns that prices have disconnected from fundamentals, prudent observers should recognize that the market structure is breaking down under stress it was never designed to handle.

This is not an analysis of a commodity market experiencing temporary tightness. This is a reconnaissance report from the front lines of a new form of economic warfare that Western policymakers and corporate strategists and institutional investors have not yet fully comprehended. China has discovered that the bureaucratic machinery of export licensing provides a precision instrument for modulating access to critical materials. It can approve allies and deny adversaries. It can grant licenses to commercial applications while blocking military end uses. It can tighten the tap during trade negotiations and loosen it as concessions are extracted. It can harvest granular data about Western supply chains with each application, mapping exactly which defense contractor needs tungsten for which munition program and which semiconductor fab requires tungsten hexafluoride for which node technology.

The licensing regime that MOFCOM implemented on February 4, 2025 covers twenty-five rare metal products across five categories including tungsten, tellurium, bismuth, molybdenum, and indium. It applies to forty-one harmonized system codes at the ten-digit level. It requires individual application for each transaction, including end-user certificates, final consumer identification, industry classifications, and technical specifications of intended use. Processing timelines extend thirty to sixty days for routine commercial applications but can extend indefinitely for dual-use classifications that trigger additional scrutiny.

This is not the blunt instrument of a traditional export ban. This is a scalpel.

The sophistication of the approach reflects institutional learning accumulated across a sequence of mineral restrictions that has unfolded with accelerating frequency. Gallium and germanium licensing began in July 2023. Graphite controls followed in October 2023. Antimony restrictions came in August 2024, escalating to a full ban on U.S. military end-use in December 2024. Tungsten controls arrived in February 2025, calibrated to land precisely as American tariffs on Chinese goods took effect. Medium and heavy rare earth restrictions expanded in April 2025 and again in October.

Each successive restriction builds on the previous. Each demonstrates greater precision in targeting Western vulnerabilities while minimizing disruption to China’s own industrial base and commercial relationships with non-adversarial nations. Each provides more data about how Western supply chains respond to restriction, information that informs the calibration of the next escalation.

The pattern suggests not reactive retaliation but proactive strategy. China has been building a mineral warfare capability for years, testing components, refining mechanisms, accumulating leverage that can be deployed when strategic circumstances require. The restrictions announced in 2023, 2024, and 2025 are not isolated policy responses to specific trade disputes. They are nodes in an integrated campaign that targets the precise bottlenecks where Western industrial capacity depends most heavily on Chinese supply and where alternatives are most difficult to develop.

Tungsten is not the final escalation. It is another proof of concept. Another demonstration that supply chain concentration creates geopolitical leverage that Beijing is prepared to exercise. Another reminder that decades of efficiency optimization through global supply chain integration have created vulnerabilities that adversaries can now exploit.

The question for Western policymakers and corporate strategists and institutional investors is not whether to take this seriously. The price charts and inventory reports and production disruptions have already answered that question. The question is what to do about it and how quickly action can translate into meaningful supply security and whether the gap of vulnerability can be navigated without catastrophic consequences for defense readiness and semiconductor production and industrial manufacturing capacity.

The answers are not encouraging.

II. THE PHYSICS OF IRREPLACEABILITY

To understand why tungsten cannot simply be substituted when supplies tighten requires understanding what makes it unique among elements. This is not marketing rhetoric from mining promoters or special pleading from industry lobbyists. This is physics.

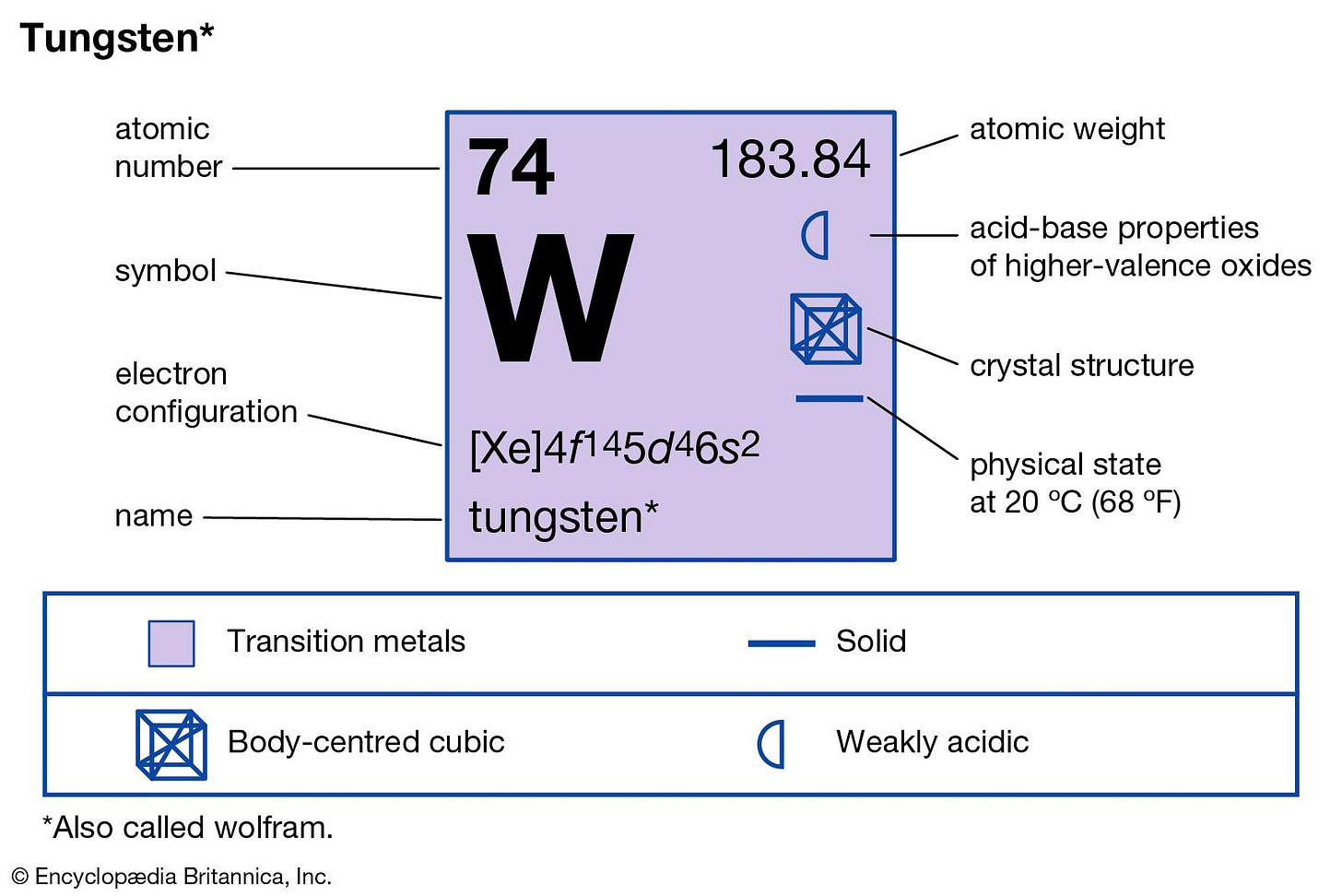

Tungsten sits at atomic number seventy-four, positioned in the periodic table among the transition metals with properties that set it apart from every neighboring element. Its melting point of 3,422 degrees Celsius exceeds that of any other metal by a margin of more than five hundred degrees. Only carbon, in its diamond and graphite allotropes, melts at higher temperatures, and carbon lacks the metallic conductivity that industrial applications require. Tungsten boils at 5,555 degrees Celsius, giving it the highest boiling point of any element. Its density of 19.35 grams per cubic centimeter places it among the heaviest materials available in commercial quantities, exceeded only by osmium and iridium and platinum group metals that cost orders of magnitude more and exist in far smaller supply.

These properties are not arbitrary. They emerge from tungsten’s electronic structure, specifically the partially filled 5d orbitals that create extremely strong metallic bonding between tungsten atoms. Breaking those bonds requires enormous energy input, which is why tungsten remains solid at temperatures that vaporize most other metals. The same electronic structure that creates those bonds also makes tungsten exceptionally hard and resistant to deformation under stress.

When a kinetic energy penetrator strikes the composite armor of a modern main battle tank, it must maintain structural integrity while decelerating from velocities exceeding 1,500 meters per second. The forces involved are extraordinary. Lesser materials mushroom or shatter. Tungsten heavy alloys, with their combination of extreme density and hardness, can survive these forces while maintaining the needle-like profile necessary for penetration. There is no other material that provides this combination at an acceptable cost and in sufficient supply for military procurement.

Depleted uranium offers superior ballistic performance due to its self-sharpening properties, but DU is politically restricted by many NATO allies including Germany and Japan, whose militaries rely exclusively on tungsten heavy alloy penetrators for their tank ammunition. The DM53 and DM63 rounds used by Leopard 2 tanks require tungsten. No tungsten, no penetrators. No penetrators, no armor-defeating capability. The causal chain is that direct.

In semiconductor manufacturing, tungsten’s role is equally irreplaceable in the near term. The vertical interconnects that connect transistors to the metal wiring layers above them must be deposited into trenches and vias with aspect ratios that would cause most materials to form voids as they fill. Tungsten hexafluoride, when decomposed through chemical vapor deposition, produces a tungsten fill that conforms perfectly to these high-aspect-ratio features. The chemistry works. The process is qualified. The yields are understood.

The semiconductor industry is transitioning toward molybdenum for some of these applications because molybdenum offers lower resistivity at the smallest dimensions where tungsten’s resistance becomes a limiting factor for device performance. Lam Research announced its ALTUS Halo molybdenum atomic layer deposition tool in February 2025, explicitly positioning it as a paradigm shift in metallization that reduces resistivity by thirty to fifty percent compared to tungsten. This transition is real. It is accelerating. It will eventually reduce the semiconductor industry’s tungsten dependency.

But the operative word is eventually. Semiconductor process qualification requires years of development, testing, and yield optimization. No major foundry is going to switch metallization materials overnight based on supply concerns. The installed base of tungsten-capable deposition equipment represents billions of dollars in capital investment. The process recipes are optimized, the yields are understood, the defect modes are characterized. Switching to molybdenum means requalifying everything, which means accepting yield losses during the transition, which means capacity constraints during the most intense period of AI infrastructure investment in computing history.

Samsung’s three-nanometer gate-all-around process has reportedly struggled with yields below sixty percent, and materials variability including tungsten supply uncertainty is among the contributing factors. When yields are already problematic, introducing additional process changes creates risk that no fab manager welcomes. The path of least resistance is to secure tungsten supply and defer the molybdenum transition until the technology matures further.

This creates a window of vulnerability that spans the next several years. Eventually the semiconductor industry will have alternatives. Eventually defense contractors will qualify new materials or develop new munition designs. Eventually the clean energy transition will find workarounds for the industrial tooling that currently requires tungsten carbide. But eventually is not now, and the supply shock is happening now.

The cemented carbide sector that consumes sixty percent of global tungsten faces the most immediate and direct impact. These are the cutting tools that machine metal parts across every manufacturing sector. Automotive engine blocks and transmission housings. Aerospace turbine blades and structural components. Medical device implants and surgical instruments. Oil and gas drilling equipment. Mining and construction machinery. Every sector that shapes metal depends on tungsten carbide tooling.

Sandvik and Kennametal are the giants of this industry, multinational toolmakers whose products are embedded in manufacturing operations worldwide. When tungsten prices rise, their input costs rise with them. Sandvik has confirmed that the high increase in tungsten prices has forced some competitors completely underwater, unable to pass through cost increases to customers who hold fixed-price contracts and refuse renegotiation. Framework agreements provide twelve months of protection for some purchases, but that protection erodes as contracts come up for renewal against a backdrop of prices that have more than doubled.

European small and medium enterprises in the tool manufacturing sector face even greater pressure. The German Mittelstand, the backbone of Europe’s industrial economy, includes thousands of companies that depend on tungsten carbide for their products and lack the procurement leverage or inventory buffers that protect larger competitors. Reports indicate that thirty percent of European SME tool manufacturers have suspended orders due to cost pressures they cannot absorb. Insolvencies are rising. Consolidation pressure is intense.

This is not an abstract supply chain concern. This is industrial capacity disappearing in real time as companies that cannot source tungsten at prices their business models can sustain simply stop operating. The capacity does not pause and wait for conditions to improve. It liquidates and disperses, and rebuilding it later requires years and investment that may never materialize.

The clean energy sector adds another layer of demand pressure. Solar photovoltaic manufacturing has increasingly adopted diamond wire sawing using tungsten-core wire for slicing silicon ingots into wafers. The tungsten wire offers superior strength that allows thinner diameters, reducing kerf loss and enabling thinner wafers that reduce material costs per watt of generating capacity. Market penetration has risen from twenty percent in 2024 to approximately forty percent in 2025, with projections suggesting fifty to sixty percent penetration by 2026.

However, it is important to be precise about where tungsten exposure actually concentrates in the clean energy supply chain. The draft versions of this analysis overstated the case by suggesting that solar wafer cutting would fail without tungsten wire. The more accurate framing is that PV wafering is dominated by diamond wire sawing where the diamond particles do the cutting and the wire core provides structural support. Steel-core wire remains viable if less efficient. The tungsten exposure in clean energy is more defensibly understood through industrial tooling for EV manufacturing, cutting tools for wind turbine gear production, and potential applications in advanced battery current collectors rather than through the solar wafer cutting process specifically.

Intellectual honesty requires acknowledging this correction. The tungsten thesis does not depend on overstating any particular application. The verified facts about production concentration, import reliance, defense dependencies, semiconductor metallization, and industrial tooling are sufficient to establish the strategic importance of the supply shock. Accuracy on the specific applications strengthens rather than weakens the overall analysis.

III. THE ARCHITECTURE OF THE BLOCKADE

Understanding China’s tungsten export control regime requires examining its structure with the precision that sophisticated readers demand. This is not a simple on-off switch. It is a tunable instrument with multiple control parameters that Beijing can adjust independently to achieve specific strategic effects.