They’ve long been one of the most reliable sources of demand for U.S. government debt.

But these days, foreign central banks have become yet another worry for investors in the world’s most important bond market.

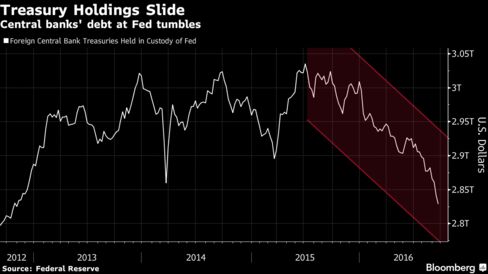

Holders like China and Japan have culled their stakes in Treasuries for three consecutive quarters, the most sustained pullback on record, based on the Federal Reserve’s official custodial holdings. The decline has accelerated in the past three months, coinciding with the recent backup in U.S. bond yields.

For Jim Leaviss at M&G Investments in London, that’s cause for concern. A continued retreat could lead to painful losses in a market that some say is already too expensive. But perhaps more important are the consequences for America’s finances. With the U.S. facing deficits that are poised to swell the public debt burden by $10 trillion over the next decade, foreign demand will be crucial in keeping a lid on borrowing costs, especially as the Fed continues to suggest higher interest rates are on the horizon.

The selling pressure from central banks is “something you have to bear in mind,” said Leaviss, whose firm oversees about $374 billion. “This, as well as the Fed, all means we are nearer to the end of the low-yield environment.”

To shield his clients from higher yields, Leaviss said M&G has scaled back on longer-term Treasuries and favors shorter-maturity securities.

Overseas creditors have played a key role in financing America’s debt as the U.S. borrowed heavily in the aftermath of the financial crisis to revive the economy. Since 2008, foreigners have more than doubled their investments in Treasuries and now own about $6.25 trillion.

Central banks have led the way. China, the biggest foreign holder of Treasuries, funneled hundreds of billions of dollars back into the U.S. as its export-based economy boomed.

Now, that’s all starting to change. The amount of U.S. government debt held in custody at the Fed has decreased by $78 billion this quarter, following a decline of almost $100 billion over the first six months of the year. The drop is the biggest on a year-to-date basis since at least 2002 and quadruple the amount of any full year on record, Fed data show.

The custodial data add to evidence that the retreat isn’t simply a one-off. Separate figures from the Treasury Department showed that China pared its stake to $1.22 trillion in July, the lowest levelin more than three years. Others, like Japan and Saudi Arabia, have also reduced their holdings this year.

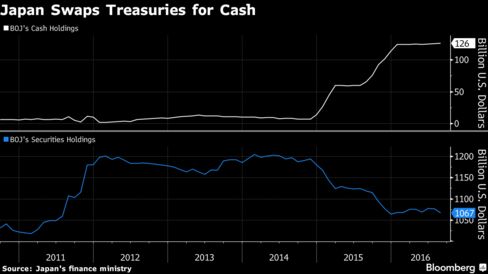

Big holders of Treasuries are selling for a variety of reasons, but they’re all tied to each country’s economic woes. In China, the central bank has been selling U.S. government debt to defend the yuan as slumping growth leads to more capital outflows. Japan, the second-biggest foreign holder, has swapped Treasuries for cash and T-bills as prolonged negative rates in the Asian nation pushed up dollar demand at local banks.

Oil-producing countries like Saudi Arabia have been liquidating Treasuries to plug their budget deficits following the collapse of crude prices. Saudi Arabia’s holdings have declined for six straight months to $96.5 billion -- the lowest since November 2014.

“Their trade position is markedly worse” because of the slump in oil, said Peter Jolly, the head of market research at National Australia Bank Ltd. That means “their need to purchase Treasuries is greatly reduced.”

The decline in central bank demand -- which some models show has cut 10-year Treasury yields by an extra 0.4 percentage point -- points to one reason that U.S. borrowing costs may finally be on the upswing after they fell to a record-low 1.318 percent in July.

What’s more, some measures suggest Treasuries aren’t providing any margin of safety.

While yields have risen to 1.6 percent, that’s still leaves many overseas investors vulnerable. For yen- and euro-based buyers who hedge out the dollar’s fluctuations -- a common practice among insurers and pension funds -- yields are effectively negative. Meanwhile, a valuation tool called the term premium stands at minus 0.58 percentage point for 10-year notes. In the previous 50 years, it has almost always been positive.

Despite those warnings, the bulls say things like tepid U.S. growth and $10 trillion of negative-yielding government debt will keep Treasuries in demand.

“It’s still attractive of course,” said Hideo Shimomura, the chief fund investor at Mitsubishi UFJ Kokusai Asset Management, which oversees about $118 billion. “People might begin to chase yields again.”

Homegrown demand has helped pick up the slack. Excluding short-term bills, U.S. money managers have snapped up 45 percent of the $1.1 trillion in Treasuries sold at government auctions this year, the highest share since the Treasury began breaking out the data six years ago. In 2011, it was as low as 18 percent. U.S. commercial banks, for their part, have also added to their investments of government debt, boosting stakes to a record $2.38 trillion at the end of August.

For central banks, “why wouldn’t they reduce their Treasury holdings?” said Mark Holman, the chief executive officer at Twentyfour Asset Management, which oversees $9.8 billion. “There is yield available there, but you have a Fed that’s been reasonably clear in what it wants to do -- it’s looking to hike.”

Whatever the case, there’s little doubt that America’s borrowing needs will only grow with time -- and that could add up to hundreds of billions of dollars in additional interest if foreign demand doesn’t hold up.

The Congressional Budget Office forecasts the U.S. deficit will rise to $590 billion in the fiscal year ending Sept. 30, the first annual increase since 2011. Over the next decade, successive shortfalls to cover costs for Medicare and Social Security will cause the public debt burden to balloon to $23 trillion.

“It’s just the beginning,” said Park Sung-jin, the head of principal investment at Mirae Asset Securities Co., which oversees $8 billion.